Marc Andreessen recently said that venture capital might be one of the last jobs. I don’t agree with the conclusion, but I think the line of thinking is directionally correct. In a human civilization, it should still be humans deciding what matters—politically, ethically, economically. We should be the ones choosing which futures are worth building. And in a world increasingly shaped by AI, I doubt the oligarchs of tomorrow will be machines.

I could be wrong. But if we’re headed toward a society still led by humans, we should start paying closer attention to the uniquely human skills that matter most. I contend that the future belongs to those with adaptability, psychological insight, and taste.

It feels like we’ve rediscovered fire—a universal unlock that changes the rules. With AI, the raw tools of creation are in everyone’s hands. The traditional moats—proprietary data, distribution, economies of scale, network effects—still matter, but early-stage barriers are melting. What once took a team and millions of dollars can now be built in a weekend. The playing field is flatter than ever. What separates people now isn’t access, but judgment.

Taste isn’t just personal preference.

It’s pattern recognition layered with values—the ability to sense what will resonate, what’s culturally or emotionally meaningful, what has staying power. It’s a byproduct of deep exposure and synthesis: art, music, architecture, product design, philosophy, history, markets, human behavior. It’s what lets someone say “this is good” long before we see the numbers.

This helps explain why senior engineers often get more out of LLMs than junior ones. Not because they know more syntax, but because they know what good looks like. They can guide an AI model toward the right answer because they’ve seen enough to recognize when something’s off. Their edge is taste.

The same applies to great founders too.

Tools are abundant, capital is arguably more accessible than ever, and AI has lowered the cost to build. But the founders who break through are those with refined judgment—those who can make creative, strategic, and product decisions that feel right before there’s proof. Founders with taste don’t just build; they shape what they build with intention.

It’s also true in early-stage venture.

There’s no spreadsheet to lean on. The product barely exists. The market might not even be real yet. The job is to spot something raw and believe in it anyway—to see clarity in the founder’s thinking, originality in the approach. In that way, early-stage investing resembles art criticism more than financial analysis.

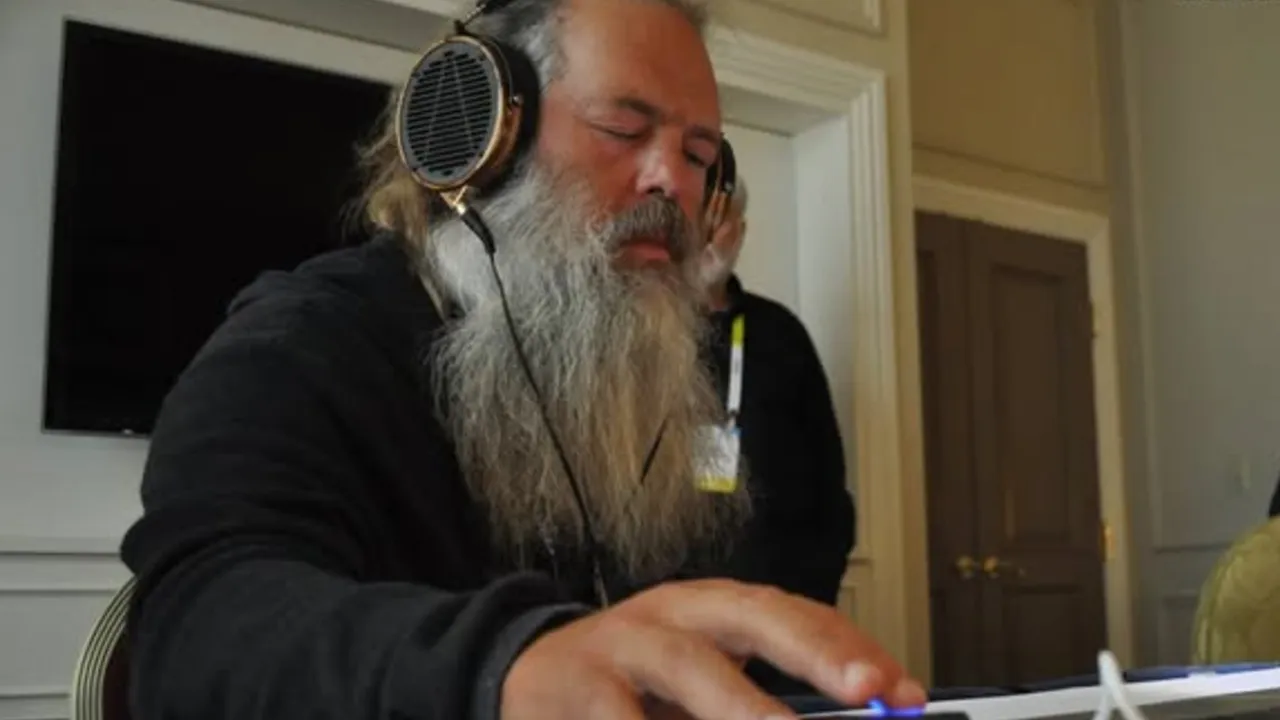

In a now-famous 60 Minutes interview (clip here), Rick Rubin says: “I have no technical ability and I know nothing about music.” He can’t play an instrument. He doesn’t know how to work a soundboard. Instead, he’s decisive about what he likes and what he doesn’t like.

Rubin gets paid for his taste. For being able to sit in a room and feel what’s true. He doesn’t create the sound, but he helps artists find it—because he knows how to recognize it when it shows up.

That sounds a lot like what thoughtful founders aim to do—and what early-stage investors hope to spot.

So maybe Marc is right. Maybe venture is one of the last jobs—not because VCs are uniquely important, but because in a world where anyone can build anything, the rarest skill will be knowing what’s worth building.

The rarest edge may belong to those who can spot it early—or build it themselves—and have the courage of conviction.